Censoring the Voices

Censorship. “The suppression or prohibition of any parts of books, films, news, etc. that are considered obscene, politically unacceptable, or a threat to security” (Oxford Languages). The practice of censoring information has been around since 443 BCE, when the “Office of Censor” was established in Rome to regulate the morals of citizens, but is most prevalent in history during and after WWII. Specifically, censorship by external means and self-censorship show up in communications such as letters, news outlets, and official government information sources. Since World War II, censorship in letter writing and communication has changed in the aspects of government control of the media but has remained stagnant in elements of self-censorship and, situationally, freedom of speech. To analyze the similarities and differences, a compare and contrast format will be most helpful in explaining censorship “then” vs. “now”.

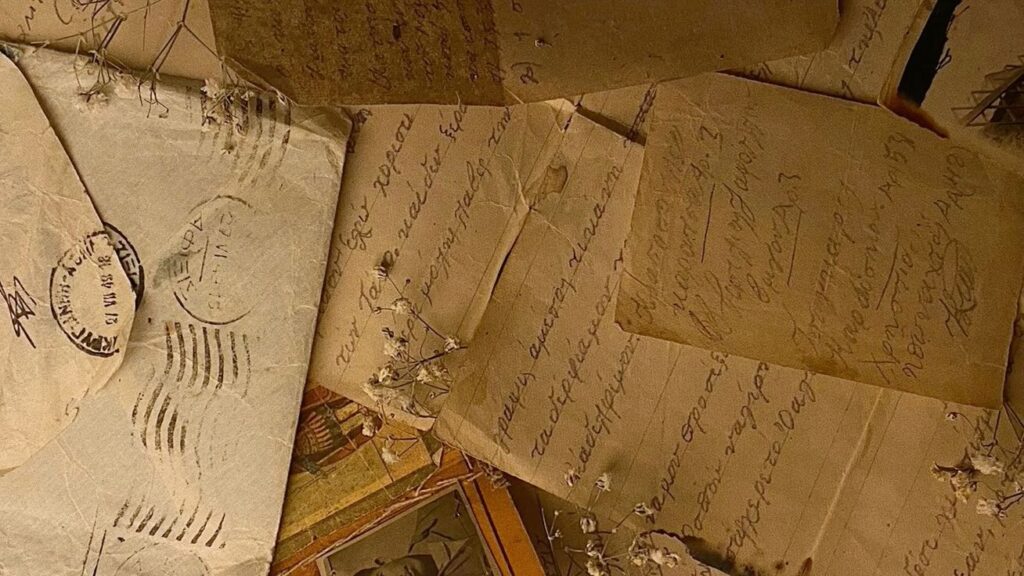

During WWII, censorship in communication and self-censorship existed through specific evidence such as letters from the Holocaust, letters from children in Japanese internment camps, and information describing the history and conditions of each.

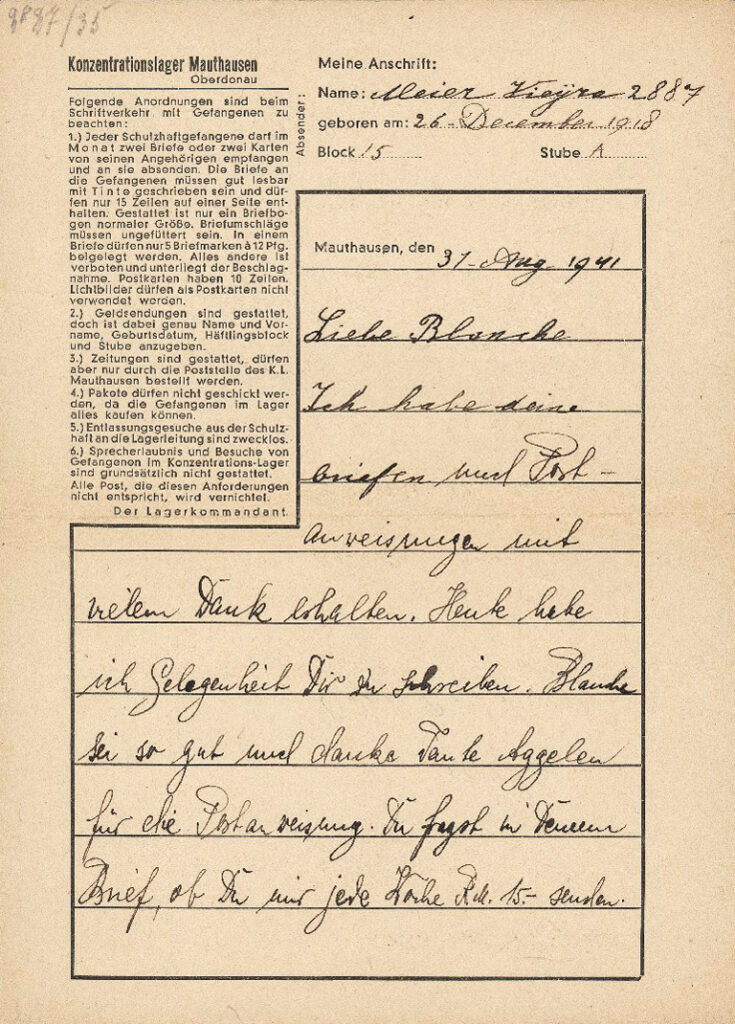

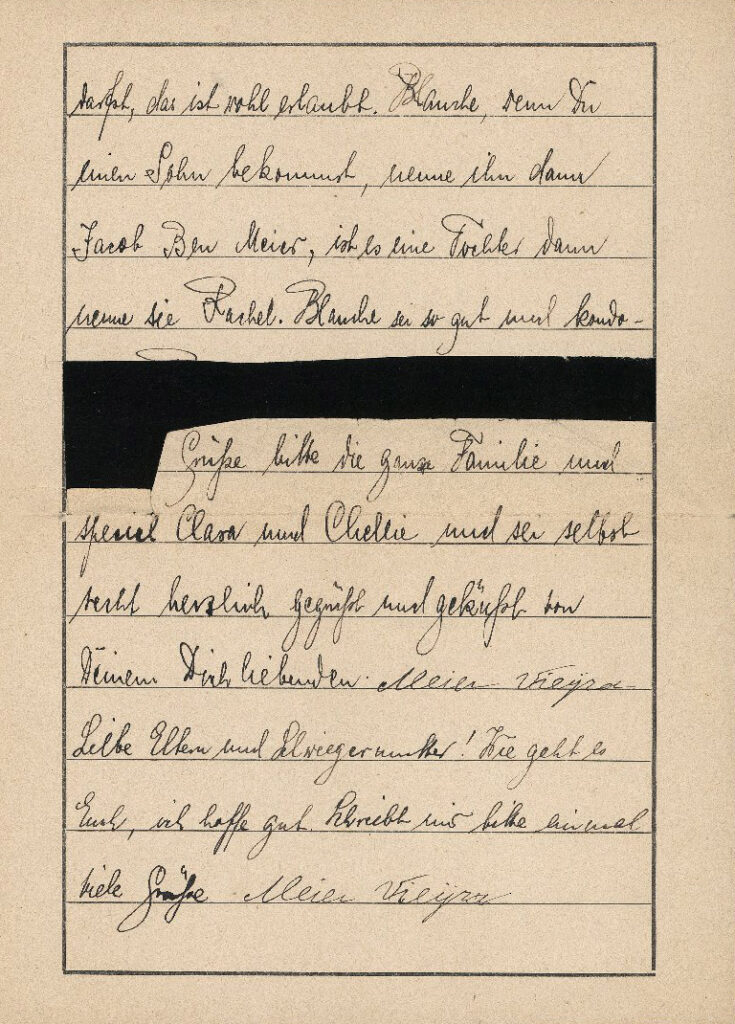

In the most explicit example of censorship, a letter from the Holocaust features sentences that are blacked out in ink. From a letter written by Meier Vieijra, a Jewish man in a concentration camp, “If it is a girl, name her Rachel…[Censored text]…Please send regards to the entire family…” (31 August 1941 – Last Letters). Featured in the backstory with the letter, it explains that the censored piece involved discussion of a loved one who had been murdered at the same camp. There is also information that suggests the handwriting in the letter was “…not Meier’s. Only the signature is in his own hand” (31 August 1941 – Last Letters). In reading the letter and the backstory, I was shocked to learn that even speech about the death of a family member was removed from texts. I find it hard to imagine how the recipient of the letter would feel not knowing what the person taken from them was trying to communicate; it must’ve been detrimental to their mental state.

In Japanese internment camps there were similar guidelines as to what a person could include in their letters. From an article focusing on the censorship of “enemy” mail in WWII, the text reads, “…regulations distributed on January 7, 1942, listed twenty-two subjects that would lead to deletions or condemnation of the letter. For example, writers were forbidden to complain about camp conditions or the individual treatment they received, including medical care” (Return to Sender). The author also explains that writers were not allowed to disclose any information regarding camp policies or to criticize the government in any way. This is showcased in letters from children living in internment camps, as they write about the positive experiences they had or specific details about daily life. Through many letters, I noticed a theme of optimism: the children seem surprisingly happy, something I would not feel in their situation. I imagine that, other than the barriers they face from writing regulations, they are attempting to make the best of things. I wonder how their parents played into this, if they were purposely making light of situations as if to make their children feel more secure in this uncomfortable time.

In both the letters from the Holocaust and Japanese internment camps, I am interested to know if writers are choosing to restrict themselves, or practicing self-censorship. This is a question I remember thinking while reading, as I saw many examples of this as people would downplay their feelings and over-express that they were “doing just fine.” In a letter from Anne Meininger, a woman in the Les Milles concentration camp, she writes, “… I am truly all right. You at home don’t need to worry about me. … The main thing is that we can receive news from each other” (30 August 1942 – Last Letters). Similarly, an article about restrictions in letter writing at Japanese internment camps speaks to reasonings for self-censorship. It reads, “Letter writers knew from the outset that their outgoing letters, submitted to headquarters in unsealed envelopes, would be read by their captors. Fear that their only connection to the outer world could easily be cut off no doubt contributed to conformity with the rules” (Return to Sender). In both of these situations, there is a pattern where writers felt as if they had to portray a happier and more “okay” version of themselves to the recipients. While some wording might be governmentally restricted, much of it was not.

In society and media today, censorship in communication and self-censorship survive through government control of free speech and social media.

In the 21st century, it is not unknown that some countries struggle with dictatorships and overpowering governments. To emphasize this, Ananyev, Maxim, et al. describe how government and censorship are tied, “…in authoritarian regimes, new technologies might mean more advanced censorship techniques, coupled with a higher propensity of modern dictators to spend resources on censorship and propaganda.” This has been directly expressed in China’s government and how their leaders monitor journalists and the information put out, often to the point of violence or incarceration enacted upon independent writers. As a person who enjoys being caught up on media and worldly issues, I would feel extremely oppressed to be living in an environment similar to the examples. I notice a connection between censorship in China and censorship in letter writing during WWII, where the government controls the communication of damaging conditions or violence and murder to the public. Now, that is not the case in the US, but it is interesting to know that it once was.

To speak upon self-censorship in the 21st century, the article “Self Censorship on Facebook” describes the ways social media can provide us with opportunities to self-censor. It reads, “Social media also affords users the ability to type out and review their thoughts prior to sharing them. This feature adds an additional phase of filtering that is not available in face-to-face communication…” (Das, Sauvik, and Adam Kramer). On social media, I often find myself forming a post of pictures or an update, but first thinking about how my wording or my photos might look. As an example of self-censorship in my own life, I am focused on the image that my online presence portrays. Across all ages, self-censorship is common on social media: Adults are often concerned about what their children are putting online and teenagers are concerned with how they appear to others online.

Looking at censorship “then” and “now”, has anything changed? Yes, in our freedom to have opinions and private communications, but not in situations of oppressive government or the existence of self-censorship on social media. Knowing the history of censorship and self-censorship, as well as how it has transferred into the 21st century, I am concerned with the situations it might bring us. Will our governments use this against us? It is clear that some already have, but in the US we still have the right to freedom of speech. Will this change in the future as situations surrounding politics and looming conflicts progress? Essentially, we must be aware of our changing surroundings and continue to find ways to communicate with others.

Works Cited

“30 August 1942 – Last Letters from the Holocaust.” Yad Vashem, www.yadvashem.org/yv/en/exhibitions/last- letters/1942/meininger.asp. Accessed 8 Oct. 2024.

“31 August 1941 – Last Letters from the Holocaust.” Yad Vashem, www.yadvashem.org/yv/en/exhibitions/last-letters/1941/vieijra.asp. Accessed 7 Oct. 2024.

Ananyev, Maxim, et al. “Information and Communication Technologies, Protests, and Censorship.” SSRN, 2 June 2017, papers.ssrn.com/sol3/Papers.cfm?abstract_id=2978549.

Cjr. “21st-Century Censorship.” Columbia Journalism Review, www.cjr.org/cover_story/21st_century_censorship.php. Accessed 8 Oct. 2024.

Das, Sauvik, and Adam Kramer. “Self-Censorship on Facebook.” Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, ojs.aaai.org/index.php/ICWSM/article/view/14412. Accessed 8 Oct. 2024.

“Oxford Languages and Google – English.” Oxford Languages, languages.oup.com/google-dictionary-en/. Accessed 7 Oct. 2024.

“Return to Sender.” National Archives and Records Administration, National Archives and Records Administration, www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2001/spring/mail-censorship-in-world-war-two-1. Accessed 8 Oct. 2024.

Leave a Reply